As the threat of closure looms over some of the recently reopened Canberra schools, and the parents of primary school- aged students particularly, contemplate again working from home, as well as home schooling all their children, spare a thought for the farming families of the Tuggeranong Valley more than 150 years ago.

Desperate for schooling for their children, they built a slab school. They, and the fiery Queanbeyan priest, Father McAuliffe, had agitated so that the NSW Education Department would send them a teacher. Martin Pike generously donated the land, centrally located near the Tuggeranong Homestead, and the main roads, as well as near the creek, and they built the school themselves. The school opened in 1870, well before Henry Parkes had declared that there would be compulsory schooling in NSW in 1880.

Imagine their dismay when, a few years later, the school was shut, and turned into a hay shed! Supposedly, Father McAuliffe had come calling and found a state sanctioned Anglican Teacher’s Prayer Book on the desk. Having a sizable proportion of his Catholic ‘flock’ sitting in the schoolroom, the priest was about to cast the offending missal into the schoolroom fire, until stopped by the seriously concerned teacher. The school was then shut.

So, the parents agitated again, since, while it was handy having their kids home to help run their farms, they were getting no education as, unlike today, many of those parents had had no education themselves. They were given land – on the flanks of Simpson’s Hill, quite remote from most of the farms, and with no water. Undeterred they built another slab school.

Whether by accident, or design, it was deemed not well constructed, but it opened in 1878. After recommendations by one of the school inspectors, it was replaced by the current school building. But this one was constructed using some of the best designs, was made of brick and stone, and best of all, was built by tradesmen, not by parents. It opened in 1880 and is still standing strong, and I now run it as a museum.

Sifting through the mass of documentation housed in the schoolroom, snippets of school life, and home life of yesteryear come to light. A memoir written by one of the most industrious of the former pupils, Sorrel Curley, reveal some harsh conditions, especially regarding the arduous task of getting to school. She remembers arriving at school in winter with ice encrusted eyebrows. After a long walk to school, often, as Merv Edlington remembered, about three kilometres, (in his case in bare feet, aged 4), meant that the children, staggering into the schoolroom, ‘copped a caning’ for being late.

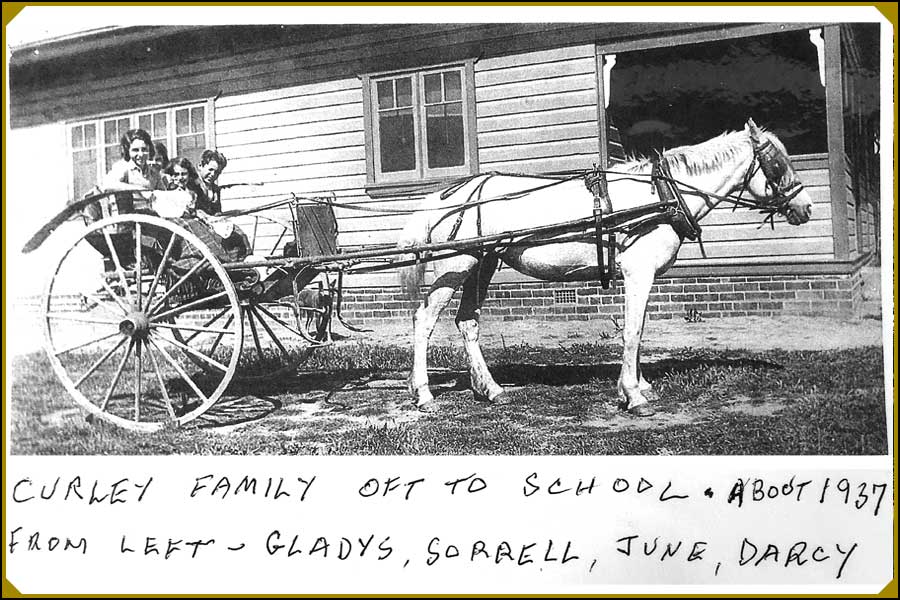

The Curley children, Sorrel, Gladys, June, and Darcy were one of the lucky families who, after one of them was considered able to control a horse, could ride to school in a sulky. Despite being thrown from that sulky, hitting her head on a rock, and lying unconscious for three days in a hospital, Sorrel went on to teach herself to type in the shelter shed which had been made from the old slab school.

Another industrious student, Bill Byrne, sick of the long hike from Tuggeranong Homestead where his dad worked came up with a brilliant solution. He was accused of ‘taking a neighbours horse without permission and riding it to school’. He got four strokes of the cane – he was 7.

Many visitors to the old school find the past escapades of the students amusing. Bill particularly features often in the Punishment Book, which, like the Confessional perhaps should remain private, but it is a great insight into the life and times of the past Tuggeranong students. Bill whistled in school and played ‘knock and run’ and by the age of 13 had had enough of school, and he went into the shearing sheds like many of his schoolmates.

Unlike most school museums there are canes so visitors can use them, on themselves of course, to fully appreciate old time ‘control in the classroom’. Six strokes of the cane were the most inflicted, and the unlucky recipient was Merv Edlington. As he remembers it, ‘We came out of school for lunch, and, of course, I was the muggins. Two or three of the other boys kidded me into going and getting a bunch of these grapes, (from the schoolteacher’s garden) - which I did. Oh Gee, they were nice too – but I got six over that!’ Merv was 12.

Somebody dobbed in poor Joseph Smith. His crime, ‘kissing girls going home from school’. He got 4 strokes of the cane – he was 7.

But there was one particular ‘stand out’ student at the Tuggeranong School. His name was James McGee. Born on the other side of the brick classroom wall, spending all his childhood in another bedroom on the other side of the wall, Jim was one of schoolmaster Frank McGee’s seven children.

He certainly did not have to trudge kilometres to school, often in uncomfortable conditions as the other Tuggeranong children did. Many of us older folk remember sitting all day in school in damp, smelly woollen uniforms, with wet, squelchy shoes, having braved the elements either walking or riding a bike to school.

Jim always worked hard in the schoolroom, was never distracted and was equally diligent at home where apart from excelling at playing the violin, taught by his expert father, he was also, with others of his siblings, an exhibition standard step dancer and an exceptional cricketer. Like others in his family, he was a keen apiarist, and rabbit trapper, earning enough pocket money to help fund his extensive further education.

After all the efforts and perseverance of the old time Valley parents to ensure that their children had the education many of them had missed, what happened to the children mentioned above?

Sorrel did exceptionally well in the burgeoning Public Service, married and had a wonderful family. She also travelled the world. Sadly, she passed away last year at the age of 96, but not before she generously donated two of her book prizes from her time at the school. They are prominently displayed in the schoolroom.

Merv became one of the most honest, hard working and hugely successful farmers in the Tuggeranong Valley, and his exploits are recorded in ‘Tracks Through Time – Merv Edlington’s Tuggeranong’, produced by the Canberra Stories Group in 1997.

Bill continued his involvement with horses, enlisting in the 7th Light Horse regiment in World War Two, after a variety of jobs including working in shearing sheds and digging trenches for Canberra’s early sewerage pipes. Ironically, whilst working as a local ranger, he lived for a time in the Tuggeranong Schoolhouse!

The last word on Bill was delivered by his elderly sister-in-law. Visiting the museum with a group from her nursing home, after they all enjoyed hearing of Bill’s youthful misdemeanours in the Punishment Book, she quietly took me aside and said, ‘Bill was such a wonderful man’.

No one knows what happened to poor little Joseph Smith. We can only hope that life was kinder to him than when he was a little chap, who had sadly misdirected his affections.

But what happened to Jim? Jim became Professor James McGee and on display in the schoolroom is a 40- page booklet which documents his many and varied scientific exploits. Despite living in the schoolhouse without running water, or sewerage and especially, without electricity, Jim became a world- renowned scientist. Apart from being involved in the development of radar and infra- red photography for the British in World War Two, Jim was also involved in the development and production of one of the greatest inventions of the twentieth century, something that changed the world, and the way we all live now – television!